Iron Mountain (Solar)

Serving Myrtle Point and portions of Coquille, Coos Bay and Port Orford at 91.9 MHz

Location: 19 miles east of Port Orford and 15 miles south of Powers (geographic coordinates and map).

Pictures were taken in June 2008.

Essential but Troublesome

The Coast Range blocked KSOR's signal from the coastal communities. The Iron Mountain translator was the central relay point for six translators from Gold Beach to Coos Bay.

There were no communities or paved roads nearby. Travel was difficult and time-consuming. During construction, we camped at the site a week at a time.

There was no commercial electrical power, and three large antenna arrays were required because of the long distances traveled by the arriving and departing radio signals. The main structure for the transmitting antennas and solar panel was large and complex. It required more than five weeks to complete the installation.

Despite the importance of this translator, there were an unusual number of equipment failures, and the solar-electric power proved to be undependable.

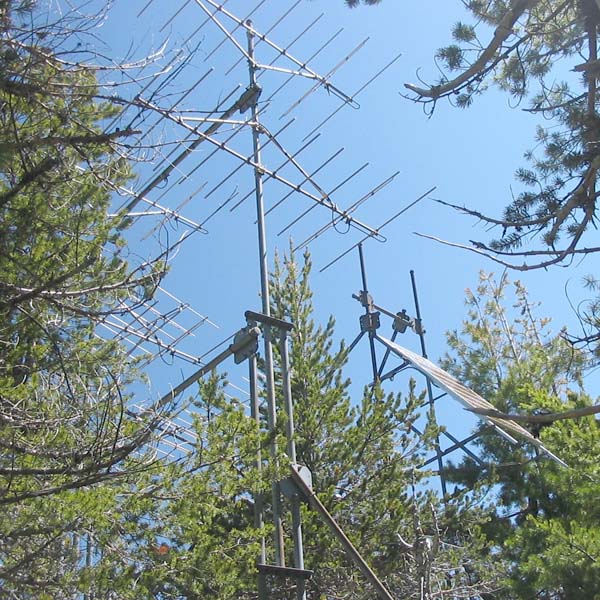

Transmitting Antennas

Six concrete anchors, each weighing about 1,200 pounds, supported six towers that rose 35 feet above the ground. Two towers supported an array of four HDCA-10 antennas broadcasting northwards to Coos Bay (seen above), and two towers supported an identical array broadcasting westwards to Port Orford. Two towers supported the solar panels.

Interlocking diagonal braces gave strength to the structure. The diagonal in the foreground supported the top of the solar-panel towers that are obscured by the tree.

Building the Structure

The antenna structure was built with minimum impact on the forest. Care was taken to remove only the trees necessary to make room for the tower bases, translator vault and battery vault. A backhoe dug the necessary holes for concrete forms.

Vehicle access to the site was limited. The truck was backed as close as possible to deliver water, cement, sand and gravel, but the final transfer was done by hand and wheelbarrow. A rented cement mixer was dragged in using the winch cable on the Dodge Power Wagon working through a pulley tied to a tree. This method of construction explains why it is now impossible to get a comprehensive view of the tower structure. There are trees everywhere!

Connecting the Receiving Antennas

Tree branches were trimmed and brush was cleared along this corridor so that the backhoe could dig a trench for the steel conduit and coaxial cable running to the receiving antennas some 265 feet to the southeast.

Receiving Antennas

The original antenna array had four HDCA-10 antennas. It picked up the signal directly from Mt. Baldy. After the transmitter was moved to King Mountain, only a single antenna was needed.

Site Selection

We did an aerial survey to gather data on a number of sites. Although the signal from Mt. Baldy was weak, we found that Iron Mountain, serving as a distribution point, would extend the signal to coastal communities with the smallest total number of translators.

There were discouraging factors to consider. Commercial electrical power was not available, and solar power would be expensive. A long drive was necessary under the best of circumstances. Winter travel would be unusually difficult because of large trees brought down by winter storms and the fact that snow depth was insufficient to support any kind of travel over the top of blocked roads and rugged terrain.

It was not an easy choice. We considered several sites while comparing installation and equipment costs, the impact on signal quality and making our best guess about maintenance difficulties.

After deciding to use Iron Mountain, we made the first of many trips by road. It would have been a picturesque outing for a vacation, but for purposes of installing and maintaining a translator, the demands in time, gasoline and repairs to the truck were quite high.

Solar Power

The solar array, pictured here and in the first picture at the top of the page, is not the original. It was larger and mounted at the very top of the vertical supports. To our dismay, it quickly proved inadequate.

The solar array, pictured here and in the first picture at the top of the page, is not the original. It was larger and mounted at the very top of the vertical supports. To our dismay, it quickly proved inadequate.

The translator was a solar powered version of the Television Technology XL10-FM2. Every circuit had been optimized to conserve electricity. A separate 10-watt module powered each of the two transmitting antenna arrays.

The solar panels provided insufficient power during the winter months. The batteries went dead and the translator ceased broadcasting. Because of this, six coastal translators also went off the air.

We had few options. First, we replaced the translator's 10-watt amplifiers with 1-watt modules. This significantly reduced the electrical power consumption. Because we had built a 20 dB fade margin into the signal paths to the Port Orford, Coos Bay and Coquille translators, we could easily afford the 10 dB loss of transmitting power. We also added two more panels to the bottom of the solar array.

In spite of these remedial efforts, the batteries had to be replaced after only five years. The puzzling circumstances of the solar-electric system failures are discussed on the Observations page.

Documents from the FCC Database

(http://www.fcc.gov/fcc-bin/fmq?list=0&facid=63102)

FCC Authorization 2008

There is no meaningful data recorded in the table of relative field values and therefore no polar plot.

Earliest Recorded License Grant 1983

Topographic Map

Ophir Mountain Quadrangle, U. S. Geological Survey

CONTOUR INTERVAL 40 FEET

Geographic Coordinates from the GPS: 42° 41' 52"N, 124° 8' 26"W (NAD27)

Antenna Height Above Mean Sea Level: 1,254 meters (4,115 feet)

Two-Way Communications Facility

Only 85 feet south of the transmitting antennas, this building and tower were the only structures in the vicinity when the translator was installed. Now, the tower has collapsed and the building is in disrepair. The turbine was still spinning in the wind, but it is doubtful there was any use for the power.

Access Road – June 11, 2008

Forest Service Road 3347 had been cleared only a few days earlier.

Winter travel is much more difficult here than at higher elevations. Snow is rarely, if ever, deep enough to facilitate travel by snowcat, snowmobile, cross-country skis or snowshoes over the top of downed trees. With no snow, it would be a terribly long walk, and navigating the fallen trees or plowing through the underbrush would leave a person exhausted long before arriving at the translator site.